Beyond Dependency: Rethinking Aid, Resilience, and Local Ownership in Afghanistan

By Ehsan ZIA, Kawun KAKAR and Omar SAMAD

Afghanistan’s relationship with foreign aid is long, complex, and cautionary. From imperial subsidies to Cold War rivalries and post-9/11 reconstruction, external assistance has shaped the country’s institutions, politics, and psyche. While aid has delivered short-term relief and supported critical services, it has also entrenched a mindset of dependency—one that undermines resilience, erodes local ownership, and weakens state capacity.

This article examines the evolution of Afghanistan’s aid dependency across three dimensions: state-building, humanitarian and development assistance, and the behavioral impacts of prolonged external support. It offers lessons for practitioners seeking to design more sustainable, locally grounded interventions in fragile contexts.

I. Aid as Architecture: The State-Building Illusion

Afghanistan’s repeated collapses weren’t caused by a lack of aid. They were driven by internal dysfunction: weak governance, corruption, factionalism, and a failure to transfer essential skills to Afghan institutions. Aid became a crutch, not a catalyst. Procurement, logistics, and administration remained under foreign supervision, leaving Afghan ministries hollow and dependent.

This dynamic was especially evident in the realm of humanitarian and development assistance. Afghanistan’s first major encounter with large-scale humanitarian aid came in the 1980s, as millions fled Soviet violence. International organizations like the ICRC and UNICEF operated within state frameworks—until those frameworks collapsed. Aid agencies then bypassed central authorities, working directly with local actors and tribal networks. While necessary, this approach weakened state institutions and set a precedent for parallel aid structures that operated independently of government oversight.

We are not claiming that all aid throughout the last century or at any interval was misappropriated, misaligned, mismanaged or wasted. A lot has been achieved over the years in terms of infrastructure and governance. Afghans are grateful for development that has been durable, sustainable and growth-oriented. As they are appreciative of humanitarian assistance when the country has faced war, displacement, drought or famine.

The trajectory has been uneven and, at times, spotty. Under the first Taliban regime in the 1990s, humanitarian access became more restricted. Aid organizations faced mobility limits, gender-based restrictions, and political interference. Yet groups like the World Food Programme and Médecins Sans Frontières continued their work, often negotiating directly with local commanders. The Afghan government, meanwhile, remained largely absent from coordination efforts.

Despite this massive investment, Afghan institutions struggled to absorb and manage aid. Much of the funding was delivered off-budget, through parallel mechanisms that sidelined national planning. Donor strategies reflected external political agendas more than Afghan priorities. Corruption flourished. Western inspectors estimated that up to 40% of U.S. aid was lost to corrupt actors. The result: fragmented projects, limited impact, and deepened dependency. Afghanistan’s aid trajectory can be divided into three major phases:

Imperial and Early State Formation (1880–1929): The British Raj in India provided financial assistance to Amir Abdur Rahman Khan to support his nascent state-building efforts; in fact, this was the first instance of foreign aid to Afghanistan ever. According to British sources, the Amir was granted “assistance in arms and money” (estimated at 1,850,000 rupees per year) with the caveat that he aligned with British advice on external affairs. These subsidies incrementally increased with his son Amir Habibullah Khan (1901-1919). The funding ceased when his grandson King Amanullah Khan declared Afghanistan’s independence in April 1919. Instead, Amnaullah was a recipient of assistance from Russia and to a lesser degree from Turkey, France and Italy. A decade later, in January 1929, Amanullah’s controversial reforms caused a conservative backlash. He fled the country, marking the end of this early period of foreign-supported state formation.

Cold War and Soviet Occupation (1950s–1989): With the rebels crushed and a return to a more authoritarian rule under Nadir Shah by 1930, the country entered a new phase of stable authoritarian rule with aid continuing to come from the USSR, Germany and Turkey. With the onset of the Cold War, competition shifted mainly to US-USSR posturing, In contrast to United States aid that amounted to approximately $500 million during the 1950-70s period, it is estimated that Moscow provided more than $2 billion in economic and military aid, making it Afghanistan’s largest donor and key development partner (Rubin, 2002; Saikal, 2004). This equilibrium tipped after the communist-led military coup d’etat in 1978. During the East-West competitive period, Western aid was almost entirely non-military, while the Eastern bloc was a mix of military and developmental. This coup laid the foundation for deeper Soviet involvement which escalated dramatically after a country-wide resistance culminated in a full-scale military intervention of 1979.

As a result of the coup and the invasion, Afghanistan became heavily dependent on Soviet military and economic assistance. Throughout the 1980s, the Soviet Union provided the regime in Kabul with at least $1 billion annually supporting both military and civilian expenditures. However, after a devastating campaign that left more than one million Afghans (and at least 15,000 Soviets) dead, Moscow ‘s new crop of reform-minded leaders began to withdraw their forces in 1989, subsequently cutting off aid by 1991 amid the USSR’s own internal collapse. As a result, the beleaguered leftist regime in Kabul facing a growing insurgency, lost its principal source of survival (Coll, 2004; Kakar, 1995), leading to collapse in 1992. The Soviet withdrawal also meant the end of the largest covert operation (mostly involving weapons and humanitarian refugee assistance) to the anti-Soviet Islamic fighters. What ensued was factional war over control of Kabul, partially supported by regional rivals.

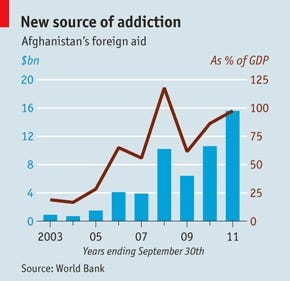

U.S./NATO Engagement (2001–2021): By the time the U.S. returned in 2001 after the terror attacks of 9/11, Afghanistan’s aid landscape was deeply fragmented. Rebuilding state institutions and restoring government ownership became central goals—but proved elusive. Between 2001 and 2019, the U.S. alone appropriated over $132 billion for reconstruction. At its peak in 2011, annual assistance hit $15.3 billion. By 2019, aid accounted for more than 75% of Afghanistan’s GDP. None of these figures include the staggering total cost of the war on terror that is estimated at more than $8 trillion.

Yet despite this scale, Afghan institutions remained weak, corrupt, and dependent. When foreign forces withdrew, the state collapsed—again. By 2022, the new unrecognized de facto Afghan state went into survival mode, demonstrating that two decades of foreign-backed state-building had failed to secure long-term stability.

As this paper was being researched, the current Afghan de facto authorities unveiled a five-year national development strategy. While the new plan is under review by experts and stakeholders, Islamic Emirate officials explained that the plan covers 10 key sectors, including economy, agriculture, natural resources, energy, housing and social affairs, transport and communications, education (which is still imposing restrictions on girls’ access to secondary and higher education), health, culture, social protection and environmental conservation.

While the plan seems to lay out 15 priority programs, initial feedback shows that there are gaps that need to be addressed in terms of professional and trained cadres that can manage the technical, financial and administrative requirements of proposed programs.

In short, looking back, each phase reveals a pattern: aid arrives with strategic intent, sustains fragile regimes, and departs when interests shift—leaving behind institutional vacuums and societal disillusionment.

II. Humanitarian Aid: Relief Without Reform Afghanistan’s humanitarian aid landscape mirrors its state-building experience — fragmented, donor-driven, and often disconnected from national planning.

1980s–1990s: Aid surged following the Soviet invasion and civil war, with millions displaced. Agencies like ICRC and UNICEF operated within state frameworks until governance collapsed. They then bypassed central authorities, working through tribal networks and cross-border channels. This weakened state legitimacy and set a precedent for parallel aid structures.

Taliban version 1 era (1996–2001): Humanitarian access became restricted. Aid organizations faced mobility limits, gender-based restrictions, and political interference. Despite these challenges, groups like WFP and MSF continued operations, often negotiating directly with local commanders. The Afghan government played a minimal role.

Post-2001 Reconstruction: Aid expanded dramatically. By 2007, over 14,000 projects were financed through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. Yet much of this aid was delivered off-budget, through parallel mechanisms that sidelined national institutions. Donor agendas often reflected political and security priorities rather than Afghan development needs.

The result: short-term gains in service delivery, but long-term erosion of state capacity and accountability.

III. Dependency by Design: The Behavioral Impact Afghanistan’s aid dependency is not just institutional, it’s behavioral. Decades of external support have shaped societal expectations, governance norms, and economic habits in ways that reinforce reliance.

Fiscal Dependency

Over 70% of the national budget was donor-funded. This undermined domestic accountability and enabled mismanagement, as locally generated revenues were often diverted by senior officials.

Institutional Dependency

Government ministries relied on international actors for core functions—planning, procurement, service delivery. Donors established parallel systems like Provincial Reconstruction Teams, which substituted for weak ministries and reduced local ownership.

Security Dependency

Afghan security forces were almost entirely dependent on foreign funding, training, and logistics. National defense was outsourced, leaving the country vulnerable when support ended.

Societal Dependency

Communities grew accustomed to donor-funded services, eroding incentives for local problem-solving. Aid shaped behaviors and expectations, fostering a belief that progress was impossible without international intervention.

IV. Lessons for Practitioners: Toward Resilient Development

Afghanistan’s experience offers hard lessons for development practitioners:

=> Embed Local Ownership Aid should reinforce—not replace—national institutions. Investments must focus on building local capacity rather than creating parallel systems. Domestic revenues should be safeguarded and strategically allocated by Afghan economic and development experts who can translate vision into actionable policy, while actively combating waste and corruption.

=> Align with National Priorities Donor strategies must be rooted in Afghanistan’s own development agenda, not shaped by external political interests. Supporting locally defined goals ensures relevance, legitimacy, and long-term impact.

=> Transfer Skills, Not Just Funds Sustainable progress requires the transfer of technical expertise in procurement, logistics, and administration. Existing technocratic capacities should be harnessed to train and mentor others. Education—for both men and women—is the cornerstone of self-reliance and inclusive growth.

=> Foster Resilience Over Reliance Programs should be designed to promote self-sufficiency, encourage community participation, and support long-term planning. Aid must empower, not entrench dependency.

=> Reform Humanitarian Coordination To prevent fragmentation, humanitarian efforts must be integrated into national frameworks. Strengthening government oversight and coordination mechanisms will ensure that aid delivery is efficient, accountable, and aligned with broader development goals.

Conclusion: Breaking the Aid Mindset

Aid shaped not just institutions, but behaviors. It fostered a culture of expectation—where progress was seen as contingent on foreign intervention. Even as assistance addressed immediate needs, it entrenched long-term fragility.

Afghanistan’s experience reveals a hard truth: external assistance, without national ownership, can do more harm than good. Decades of war, poverty, and poor governance created fertile ground for dependency. But it was the failure to build resilient, accountable institutions that turned temporary aid into a permanent necessity.

If Afghanistan is to move forward, it must reclaim its development agenda. That means investing in local capacity, demanding transparency, and redefining aid as a tool, not a lifeline. The world must support this shift, not with more money, but with more trust in Afghan-led solutions./

Ehsan Zia is a former Minister of Rural Rehabilitation and Development, and Country Director for Afghanistan at USIP.

Kawun Kakar is Managing Partner of Kakar Advocates Law Firm, a former senior Afghan government advisor & a UN official.

Amb. Omar Samad is a Non-res Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, A Senior Peace Council and Chief Executive Advisor, Government Spokesperson, and a former Afghan Ambassador to Canada and France.

References and sources:

SIGAR: Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction http://www.sigar.mil/Reports/Quarterly-Reports/Funding-Tables/

SIPRI: 20 Years of U.S. Military Aid to Afghanistan https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2021/20-years-us-military-aid-afghanistan

CRS Report: Afghanistan Reconstruction Funding https://www.congress.gov/crs/products/IN11728

World Bank: Afghanistan Country Overview https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/overview

ForeignAssistance.gov – U.S. Aid Dashboard https://foreignassistance.gov/cd/afghanistan/

Transparency International: Corruption Perceptions Index – Afghanistan https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/afghanistan

IDS Report: Aid Dependency and Political Settlements in Afghanistan https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/aid-dependency-and-political-settlements-in-afghanistan

CSIS: The Future of Assistance for Afghanistan https://www.csis.org/analysis/future-assistance-afghanistan-dilemma

Afghanistan Analysts Network: Aid Effectiveness Review https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/economy-development-environment/the-state-of-aid-and-poverty-in-2018-a-new-look-at-aid-effectiveness-in-afghanistan/